KONSTANTIN ZHUKOV

23 FEB - 23 MARCH 2024

black carnation part three

-

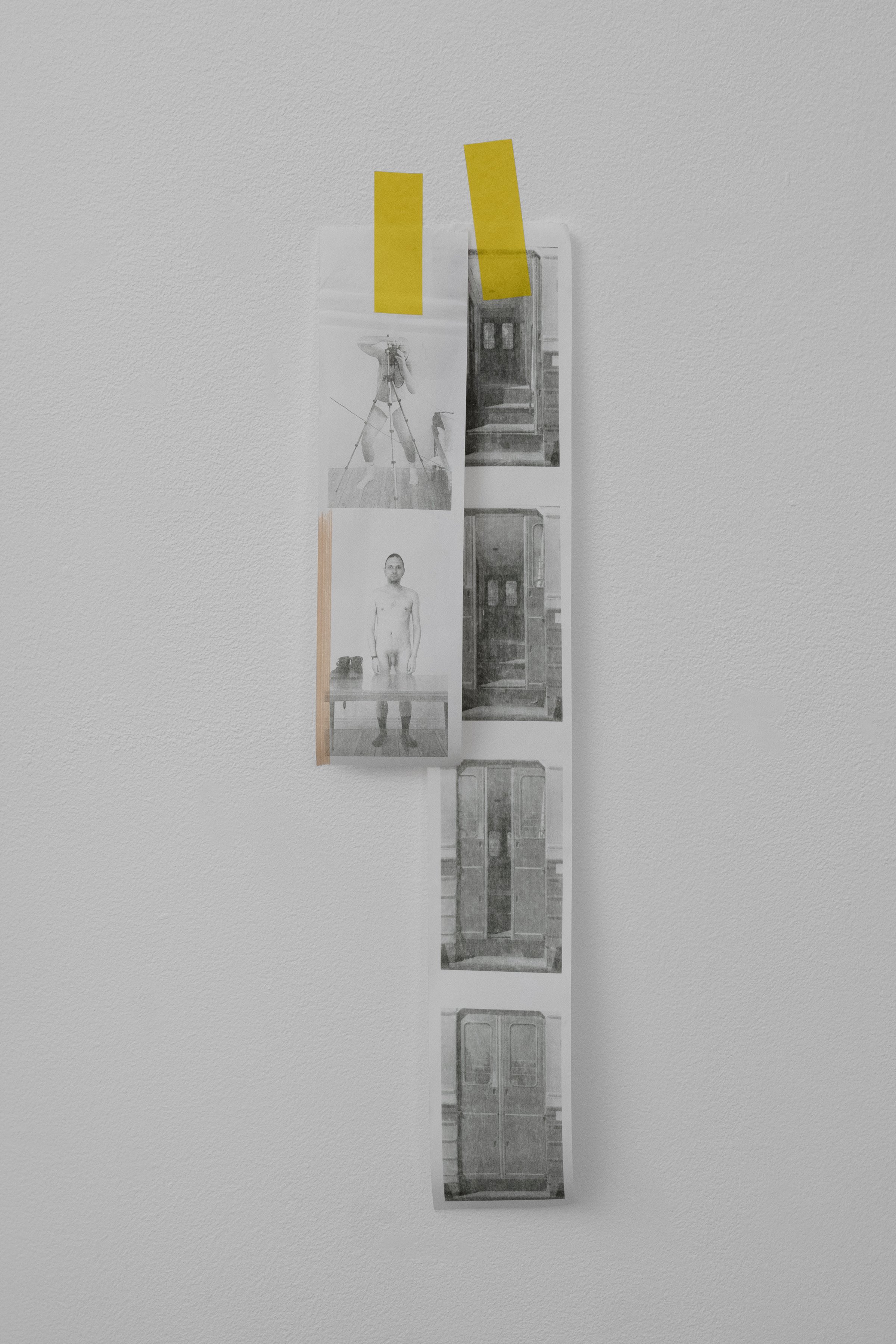

‘Black Carnation Part Three’ is the debut UK solo of Latvian artist KONSTANTIN ZHUKOV, and the third instalment of the artist’s ongoing Black Carnation Project which investigates and reflects on the poorly documented queer histories of twentieth-century Latvia. This tension between presence and absence, as well as indexes of touch, are through lines in Zhukov’s works: sitters appear and disappear from view; a bowl, once containing apples, sits empty; white socks are left discarded on the floor. In a nod to the Soviet interior, the gallery walls are painted halfway, recalling the decor of institutions and communal apartments at the time. Zhukov reflects on the ambiguity between private and public in these shared spaces, which historically rendered queer intimacy near impossible.

The faded painterliness of the images, printed onto the same receipt paper used for train tickets, speaks to the state of Latvia’s queer archives and to the nature of memory itself; a transience, a softness, a fuzzy edgedness. In ‘Black Carnation Part Three’, Zhukov presents a layered and complex tableau of history and legacy, interrogating which stories are historically erased or forgotten, as well as reflecting on broader themes of longing, intimacy and everyday tenderness.

The exhibition is accompanied by a soundpiece commissioned from Latvian electronic band Alejas.

-

KONSTANTIN ZHUKOV (b.1990, Riga) is an artist living and working between Riga (Latvia) and London (UK). His creative practice is informed by his research into recorded and oral histories of different forms of attachment and sexualities. Most recently, Zhukov has turned to the scarcely explored and poorly-documented queer histories of his home country, Latvia, which form the basis of the ongoing Black Carnation project.

Zhukov was the subject of a solo show at ISSP Gallery, Riga (2022), and has been included in group shows at Blanc Art Center, Beijing (2023); Cromwell Place, London (2022); and hosted a talk on Latvian queer histories at Lafayette Anticipations, Paris (2022). He is currently exhibited at LCC (Latvian Centre of Contemporary Art), Riga, and is included in upcoming shows at MO Museum, Vilnius (March 2024), the Latvian National Museum of Art, Riga (April 2024), ISSP Gallery (Summer 2024) and ‘Survival Kit’, the annual festival of contemporary art organised by LCCA, Riga (Sept 2024). Zhukov’s work has been published online and in print, including i-D, CAP74024, and now-closed ‘Открытые’ (o-zine.ru), a progressive LGBTQ+ publication based in Moscow.

-

YATES NORTON Could you tell me a bit about your ongoing Black Carnation project and how this body of work came into being?

KONSTANTIN ZHUKOV I’ve long been looking into the stories and lives of queer individuals. A few years ago, I ended up back in Riga after almost a decade spent in London. It was a self-initiated residency of sorts. My experiences as a gay man had predominantly been formed in London, and I wanted to see what I could find out about queer histories in my home country. What I found is that there is a near absence of preserved queer history in Latvia. The Soviet period is the biggest blindspot of the 20th century. Pre Soviet occupation, there was a freer press and we have more stories preserved from that time, but it’s more like gossip.

YN The term Black Carnation comes from this pre-Soviet era, right?

KZ Yes, Black Carnation was a term used to refer to gay men in the 1920 and 30s, the interwar period of the Latvian Republic before the Soviet occupation. The term was subsequently lost, and rediscovered by the researcher Ineta Lipša. We don’t know if homosexual men used it between themselves, but it does appear in gossip press of the time, particularly in relation to the so-called Black Carnation Club case from 1926, which was a criminal case in which several men were accused of pederasty, as it used to be called back then. The case revolved around a flat in old town Riga which functioned as a kind of underground brothel where homosexual men could meet. The first exhibition of my work on the so-called Black Carnation was in an exhibition space next to where that house used to stand. I drew parallels between the online cruising happening on Grindr today and the activities of the Black Carnation Club. The second part of the project investigated topics that defined queer lives in the 20th century: medicine, law, the survival mechanisms of cruising and modes of communication. This third part is perhaps less illustrative, in that I’m trying to reflect on this sentiment of absence, this sparse archive.

YN As you just said, queer history in Latvia is being researched as you are developing this project, but it’s mainly academic, revolving around oral histories. Your work is complementing that research through a visual language that is taken from multiple, intimate and everyday sources. It isn’t just about testimonies and court cases or what’s missing from the archive. You seem to be showing us that there have always been sensual encounters between men, encounters that are fleeting and fade, just as the images you print on the receipt paper quite literally fade. But your works don’t strike me as nostalgic or mournful.

KZ I’m trying to develop these two complementary strands in my practice. One is this amateur researcher role, and the other, which is shown here, is a visual exploration of wider themes. I’m happy to hear that it doesn’t feel nostalgic. I guess the work that I’m creating is a commentary on the past, but also speaks to today. When we look at history, even in the most oppressive of regimes, people found ways to live and find joy. My sitters are queer people living in Latvia today, and it feels meaningful to them to see themselves represented in a country where same sex civil unions are only just about to be recognised this summer. We’ve had Gay Pride since joining the European Union, yet people would throw actual bags of shit at people marching.

YN Your sitters are your contemporaries, so how does that relate to a queer history of Latvia?

KZ I really enjoy the social aspect of my practice. I know about cruising spaces from meeting people and going with them. They show me the shortcuts. They tell me when the busiest times are, when the quieter times are. They recall memories there. The older generation tell me where they used to cruise, spaces that have since been gentrified or privatised. So there are histories to be uncovered through others. I enjoy that. When I work in the studio, I always talk with the sitter before we shoot. I show them my findings and some of my research, and it often becomes a mutual reflection on these histories. Photography, like cruising, produces encounters that are sometimes very brief, and happen once. I actually rarely return to the same sitter. There are always new people who either reach out to me, or who I reach out to, or that I find by chance. My practice is so based in the past and its research, but it’s also about today.

YN I think the terms of my question assumed wrongly that history has a past and a today, a ‘then’ and a ‘now’ and, of course, it’s much messier than that. What you’re offering us is more like a collage of memories and present-day encounters which show how the past comes into the present and the present reflects on and inflects the past. There’s this really lovely quote from José Esteban Muñoz who writes on John Giorno’s exuberantly erotic stories of queer encounters as: ‘a life that both was and never was, that has been lost and is to come. And it is all these things at the same time.’

KZ I guess the past is the inspiration, the starting point to the work.

YN Queer narratives are often sensationalised or eroticised in a two-dimensional way, but what you show is a kind of everydayness and stillness. This comes through in the couplings of your photographs: people are paired with a bowl of fruit, a glass of milk... Is that sort of pairing with everyday objects about underscoring that the kinds of lives and encounters you want to describe and record are in some way profoundly ordinary? As a queer person, the tenderness and everydayness of your work is very powerful to me, because so much of queerness is in the hush and in the ordinary, and in an eroticism that is multiple and shifting, in different ways of touching and being with one another.

KZ I was thinking a lot about how perishable we are and what gets left behind. The warmth of a body left momentarily on a seat, the marks on the glass that stay until the next dishwasher cycle. We are a sum of very small everyday marks. I was recently reading a conversation with Lucian Freud which read his work as dependent on the consumption of other living organisms, like we ourselves depend on consumption for survival, whether it’s a piece of meat or an apple. An eaten apple, for example, could mark a person’s presence. Yet the absence of a body speaks to how we preserve queer history, that we have to look for it in the cracks, to read between the lines, to seek it out in the traces that it has left behind.

YN The works offer up the possibility of telling a story, several stories. You have photographs that look like they’ve been gathered by a detective – but if there were to be a detective behind your practice it would be a Sherlock Holmes who’s actually more animated by curiosity in people, by gathering material to tell stories and by the sensuality of touch much more than by solving any crime. There’s poetry in this gathering, in the way that Eileen Miles defined poetry as being about collecting and salvaging, making a map of possibility for everyone, rather than trying to tell one story or narrative.

KZ You mentioned curiosity which I think is a keyword. My practice started with me trying to understand who I am and accepting my own homosexuality, but it really became about curiosity in other people, their stories, in what came before me. I am a bit of a detective in that sense. The sea became such an important place for me. I go to the cruising beach with big IKEA bags to collect things I find there and imagine the stories and people behind them.

YN The installation at NEVEN brings together elements of the domestic as well as references to that beach. Could you talk about these elements and how they come together?

KZ I was thinking about queer Latvians’ relationship to home. During the Soviet period, domestic spaces were often shared, so private space wasn’t actually private and queer people had to look for intimacy outside. So places like the cruising beach became a kind of home. Private became public and vice versa. The raskladushka, a Soviet folding bed, featured in the show speaks to the transience of bodies passing through space. For queer people in the 20th century, who couldn’t enjoy romantic intimacy in the home, fleeting encounters were relied on.

YN I I think what you show is that there is something freeing in this fleetingness. You told me that to get to the cruising beach, you take a train. It reminded me of Giorno describing having sex in a public toilet and then getting on the subway, and it feeling like a cage of heteronormative misery, all brightly lit, everyone looking depressed. A train itself is the straightest thing, because it literally has to go on a straight line to get from A to B. But then cruising is so winding and curious and makeshift and this gives it an energy that is full of possibility.

KZ To me, the train ride is a very positive part of the journey, a time for preparation or for afterthoughts. But loneliness and isolation are definitely part of the work. An important reference for me is a recently published diary of a queer man called Kaspars Aleksandrs Irbe who was born in 1906, just before Latvia gained independence. He lived through the democratic period, then through all the occupations and eventually the first years of renewed democracy after the fall of the Soviet Union before he died in 1996. His diary is one of the very few documents we have telling us about gay men’s experiences during those times. He describes cruising in the park, then coming home, washing his body, eating apples from his garden and drinking milk before going to sleep. And there is this feeling of loneliness, the image of returning to your room and eating apples by yourself and not being able to share them with anyone. There is joy and there is also loneliness.

YN The images are definitely full of longing, which characterises so much of desire, queer or otherwise. The fact that they’re printed on receipt paper also alludes to something transactional, but their fading quality also brings to mind something fleeting and delicate and tender. There is a lot about touch in your work and, of course, photography is quite literally the stain of light and ink on paper –– something as untouchable as light becoming an image. Why is photography your medium of choice?

KZ Photography as a medium is a stain of light and ink, but crucially it’s heat that prints on receipt paper, so again there’s a physicality to this image production. Photography was also simply what was available to me, and I like its immediacy.

YN Although the work is about queer history and queer desire, the ordinariness that I spoke of earlier makes me feel that the work speaks generously and openly; it is diffuse and poetic, in the sense that it is less concerned with making a statement about something as following desire as something that is always questioning and observing.

KZ The work is, initially, about myself, my desires, and my curiosity, but I’m always trying to find ways to open it up. What can a person who has nothing in common with me relate to in my work? And what is the potential in that?

-