Prelude

20 October 2021. I had just come out of your old studio on Bethnal Green Road when I began reading ‘Agua viva’ (1973) by Clarice Lispector. I wrote your name beside the epigraph.

There must be a kind of painting totally free of the dependence on the figure—or the object—which, like music, illustrates nothing, tells no story, and launches no myth. Such painting would simply evoke the incommunicable kingdoms of the spirit, where dream becomes thought, where line becomes existence.

—Michel Seuphor

I

Conversations unfold chaotic, unruly, woven in real time as ideas ebb and flow, and words wrap (or not) around them. Tense draws back and forth while location shifts from past to present to future. From here to there in an instant, storylines clash, mesh, and blur together. A conversation is a wormhole, and ours is now ten years old.

In our latest call, we circled the same topics as always. Domestic life, anxiety, fragility, the rain. The hegemony of memory and how ours are forever stamped by abstract geometry. Venezuela and Alejandro Otero always seem to find their way in. We spoke of overwhelming chaos looming to no foreseeable end, the only sane responses being radical acceptance, subtle subversion, and the ventilation of friendly chat.

You tell me you want me to write about your new series of works. You say you had intuitively decided to reproduce these moments from photos you had on your phone; stills of your own clothes drying off the ocean water, hanging on the towel rails in your bathroom by the beach. You cannot yet fully articulate what they are or what they mean. The origin of an idea can often be elusive, but following the threads back towards its beginnings has always been a passion of mine.

We remark that these ladder-shaped radiators are commonplace enough in Europe, but nowhere to be seen back home. Conjuring up warmth to dry clothes in Venezuela is a nuisance; the sun does all the work. You mention a video someone recorded from inside their car while passing through Avenida Libertador, one of the main avenues in our mutual hometown. This street functions more as an artery, connecting the hustle of downtown Caracas to Altamira, the part of the city that birthed us both and saw us leave at the cusp of childhood and adolescence. The street slopes down into an open tunnel, flanked by walls proud with a mural of stacked rectangular modules, tilted slightly back and forth. Orange, black, white, gray, and yellow. If luck strikes just right, the sky is blue, and the car can speed past.

II

From the casual optical illusions of Caracas, we dive into your desire to flatten the three-dimensional, to paint with sculpture. For years, we have been speaking about your use of clothes as brushstrokes, as ways to make lines. In tension with the fabrics forever wet, immortalised in resin, there is a sense that the work is now starting to dry, like a fossil. I mention that zooming into these ladder shapes and hanging textiles, where the fibres of the clothes meet the chrome bars of the radiators, there is a microscopic grid. [Just by saying this, as if caught by non-induced psychedelia or science fiction, I suddenly take a trip into it].

In a more obvious way, though, this new body of work seems to be your most abstract, geometric attempt yet. You vaguely recall an essay you read once in pre-grad that you say has been a major influence on you. Something about magic in John MacCracken’s sculptures, something about a mirage. The allure of minimalism has sat with you all these years—you have always been able to see that behind such calculated material structures hides something much more profound, universal even. But you have had no luck in finding the text. You must still be under the effect of the recent eclipse, you say, your memory has been so hazy lately. This essay sounds so mystical that I can’t help to side-Google while you continue talking, but my audacity yields no successful results, so I take a guess: “Was it by Rosalind Krauss?”. My mind was also a bit cloudy, but evidently her essays, ‘The Optical Unconscious’ and ‘Grids’, are ingrained somewhere deep within me. [Again, the grid revealed itself in passing, haunting our conversation, proving its presence, lodged in a mysterious, inaccessible place].

The bars of the radiators also remind you of a musical pentagram, and something about your mention of sheet music makes me urge you to listen to Philip Glass. Not knowing exactly what strange impulse led me to say that, once we hang up, I search for an album of his to play in the background while I collect my thoughts. Perhaps it was just synchronicity in full effect or the most literary part of my memory recalling the fact that (of course) Philip Glass wrote a song called ‘The Grid’. It was written as part of the score for a documentary called ‘Koyaanisqatsi’ (1982). I press play and start to write.

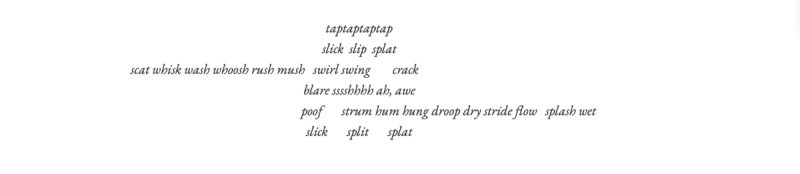

Interlude

III

As the orchestra builds from the brass instruments up, I give up trying to find the text on minimalist magic and instead delight on images of MacCracken’s glossy building-like structures, skyscraper totems aiming towards the sky, reflecting life around them. The only thing I conclude about the author is that to have been able to observe the magic in the sculptures, they certainly had the ability to look with more than just their eyes. Anyway, out of all the tabs on my browser, one does contain what I want it to: Rosalind Krauss’s ‘Grids’ (1978), ready for download. Krauss critiques modernist ambition and blames it for “walling the visual arts into a realm of exclusive visuality”. She refers to the ambivalence, especially of minimalist painters, who never distinguished their work’s connection to matter from its connection to spirit. For these artists, it was not an either/or question, it was always both. The music keeps hypnotically repeating and folding in on itself as more sections of the orchestra join in, and I finish the Krauss essay only to read in the last sentence the name of the person behind the score:

Interweaving choirs of human voices start scattering onomatopoeias in dialogue with a technological journey of synthesisers. These sounds of pleasure, ooohs, aaahs, and humms, against the tunnelled shapes of the music send me back to our first conversations about art. In 2015, you needed a second pair of eyes to read your bachelor's thesis. Questions surrounding carnal desire were already at the core of the earliest iterations of your work. Your thesis is informed by the indelible impressions of minimalist art and the failed promises of modernism on a young artist’s brain. You yearned to imbue its history (and your own) with emotion, physicality. You somehow wanted to give this modern legacy a symbolic body.

You chose then to “go back to the past to understand the present”, a phrase you still repeat. You followed your curiosity towards investigating a Venezuelan avant-garde movement born in the 1960s, ‘El Techo de la Ballena’ (“The Roof of the Whale”). A group of rebellious, exiled Venezuelan men, exhausted by cold, harsh geometric abstraction, which, to them, tragically reflected a more brutal coldness—one that occupied every realm of modern social life and had made it sickeningly superficial. They stood for a “colossal expansion of feelings and aesthetic perception, the exaltation of sensuality, apotheosis” that would widen through the range of visual arts over to poetry, performance, publishing, and manage to make its way into politics. “The whale consumes life whole”.

Perhaps it was the emblem of the whale that picked you. Years before, you had received an orange Duty Free bag labelled ‘Tesoros’. Inside the bag was an ominous manila folder filled with the self-published magazines and manifestos of El Techo. You considered treasures what others might have seen as debris.

You swam right into The Whale’s belly, studying all of the group’s references, going into the trenches of art history. You ate it all up from inside and, as a result of this gory digestion, your body was spit out and became the main character in your own work. You placed your own figure front-and-center against the backdrop of your art historical research: minimalism at its apex, spreading out towards architecture, design, and beyond; this group of poets and artists calling modernism out for its pristine, industrial, and seemingly “perfect” expressions, which they found disgusting for covering up histories of political violence. And then you, rebelling against your own memories of minimalism and geometric abstraction, taking the historical cue from The Whale and responding with poetry and performance.

IV

At some point I notice my soundtrack has been silent for a while. So I switch my attention back to the musical side of the pendulum, which demands that I explore it further. The non-narrative film ‘Koyaanisqatsi’ (1982) is the first chapter of a three-part experimental documentary series by Godfrey Reggio. It is lauded all over the grid of the internet and readily available to watch online for free—somewhat of an oddity. Images of everyday life are presented in fast, almost frantic succession. Time-lapse scenes of factories, shopping malls, pedestrian crossings, and highways are collaged with views of canyons, oceans, and natural reserves. Reggio explains: “I rip out all the elements of a traditional film (actors, characterisation, plot, story) and move the background to the foreground. I make the backdrop the subject and ennoble it with the virtues of portraiture.” The word “koyaanisqatsi” means life out of balance—the myth of progress, technology spread out in all directions, and human life existing not aided or affected by it but within it.

In the foreground of ‘Scatter Symphony’, clothes exhausted by water, droop down vertically in pure colour, like the brushstrokes of the modern masters. Despite wanting to dry, the clothes will remain wet forever because the background, technology, is paused, no longer working, no longer useful. The radiator – a flatter support for your current desires – wants to warm the world, but it cannot; it wants to reflect, but it distorts. The action, the energy, is missing—felt but not present, implied but not seen. Just like the figure who performed it is hiding beneath the background, behind the daily ritual—like a spirit. All of it is then encapsulated by resin, and then once again contained, encapsulated in a plexiglass box, as if to protect the entire body-less body from the violence of time; a box that will no doubt reflect the world around it, like John MacCracken’s monolith.

At the studio, everything had happened so fast. The initial idea was so automatic that you tried to fight it for its spontaneity, its freedom from the realm of thought. But it felt full circle, so you had to surrender. You acted out the process of taking off the clothes as if you were in the bathroom by the beach. After a day’s time had crystallised the scenes, they felt true. The re-enactment had magically worked—a performance of what Krauss attributes to modernists: “pure simultaneity”. And as the album reaches the song titled ‘The Grid’— the inescapable mythic god that Krauss seems to admonish—there is no other way to say it, the symphony reaches its orgasm.

After many twists and turns, “rinses and holds”, your work is circling back to the center of the loop, the deepest imprints of your youth—the op-art tunnel in Caracas, the authorless essay, your childhood memories clad with masterful minimalist abstraction. By exploring the nooks and crannies of your own mind, almost without noticing, you have returned to the unnoticeable. The ubiquitous and invisible often does elude us, but there is no way to escape it. The grid that connects it all stands out loudly and calls out for attention, clueing us into noticing it.

Woven into memory, enmeshed in history, and permeating absolutely everything, there is no escaping the invisible net that just is. “Like music, it illustrates nothing, tells no story, and launches no myth.” And yet it evokes the incommunicable everything.